Uterine Cancer

The uterus, or womb, is a central part of

the female reproductive system. It is a hollow, muscular, pear-shaped organ

where a foetus develops and grows during pregnancy. The lower part of the

uterus, known as the cervix, connects the uterus to the vagina, serving as a

passage between the two. Uterine cancer refers to any malignant tumour that

originates in the uterus.

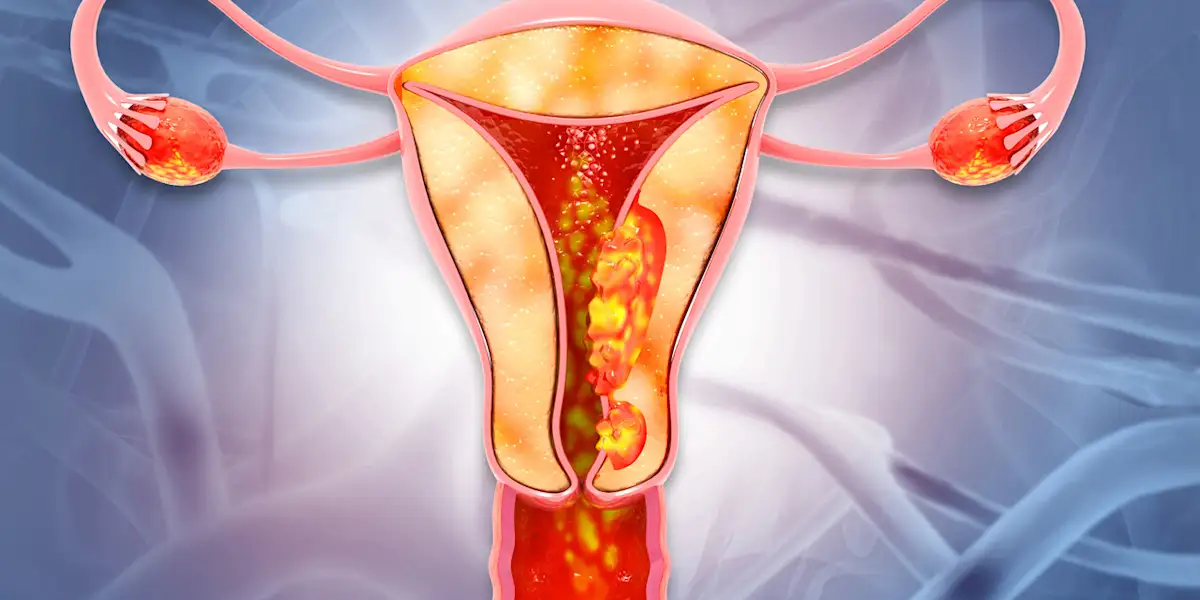

The uterus is divided into two main

sections: the lower end, or cervix, and the upper portion, referred to as the

body or corpus. Structurally, the uterus consists of three distinct layers. The

innermost layer, called the endometrium, is made up of glandular tissue

that lines the uterus and plays a vital role in pregnancy and menstruation.

Surrounding the endometrium is the myometrium, a thick layer of smooth

muscle that facilitates uterine contractions during labour and menstruation.

The outermost layer, the serosa, is a thin tissue coating that protects

the uterus and separates it from surrounding organs.

Changes to cells in the uterus can sometimes

lead to precancerous conditions. This means that the cells appear abnormal but

they are not yet become cancerous. The most common precancerous condition of

the uterus is atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia

is a condition where the endometrium becomes abnormally thick due to an

overgrowth of the cells lining the uterus. The myometrium has specific

precancerous conditions, such as STUMP and atypical leiomyomas, which can

progress to malignancy. The serosa is primarily a connective tissue layer and

is not as prone to direct malignancy or precancerous changes as glandular or

smooth muscle tissues.

Primarily there are 2 types of uterine

cancer. Most uterine cancers are endometrial carcinoma, which starts from cells

in the lining of the uterus called endometrium. If a carcinoma starts in the

cervix, it is a cervical carcinoma. Carcinomas starting in the endometrium are

endometrial carcinomas. More than 95% of uterine cancers are carcinomas.

Uterine sarcoma develops in the supporting

tissues of the uterus, including muscle, fat, bone and fibrous tissue (material

that forms ligaments and tendons).

A third type of cancer called

carcinosarcoma sometimes develops in the uterus. Another type of cancer that

starts in the uterus is called carcinosarcoma. These cancers start in the

endometrium and have features of both sarcomas and carcinomas. These cancers

were known as malignant mixed mesodermal tumours or malignant mixed mullerian

tumours.

Uterine sarcoma is a rare type of uterine cancer and aggressive group of malignant neoplasm

that arises from the smooth muscle or connective tissue of the uterus called

myometrium. Unlike other forms of uterine cancer, such as endometrial

carcinoma, uterine sarcoma originates in the structural and supportive tissues

of the uterus rather than its lining.

Sarcomas are cancers that start from

tissues like muscle, fat, bone, and fibrous tissue (the material that forms

tendons and ligaments). Cancers that start in epithelial cells, the cells that

line or cover most organs, are called carcinomas.

Various Types of Sarcoma

The below category encompasses a broader range of

uterine sarcomas that can arise from various tissues in the uterus, not just

the endometrial stroma. It includes tumours from different tissue types,

including smooth muscle and mixed tumour types. The tumours are classified

based on their histological features and tissue origin.

1. Leiomyosarcoma:

Originates from the smooth muscle of the uterus called myometrium. Most common

subtype of uterine sarcoma, highly aggressive with a tendency to metastasise,

especially to the lungs.

2. Endometrial

Stromal Sarcoma (ESS): Originates from the connective

tissue of the endometrium or the uterine lining.

3. Undifferentiated

Uterine Sarcoma: A poorly differentiated tumour,

making it difficult to determine its tissue of origin.

4. Adenosarcoma:

A mixed tumour, which contains both glandular (epithelial) and sarcomatous

(connective tissue) components. Typically less aggressive than other uterine

sarcomas, though it can still cause significant health problems.

The World Health

Organization (W.H.O) classifies endometrial stromal neoplasms

into four groups. This arise from the connective tissue of the endometrium.

These tumours are generally classified by differentiation and aggressiveness.

1. Endometrial Stromal Nodule: Benign

tumour that arises from the connective tissue of the endometrium. Does not have

malignant features and does not spread. Generally considered the least

aggressive.

2.

Low-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma

(LG-ESS): Malignant but slow-growing tumour originating

from the endometrial stroma. Better prognosis due to its slower progression and

lower likelihood of metastasis.

3.

High-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma

(HG-ESS): A malignant tumour originating from the

endometrial stroma, but with a highly aggressive nature. Characterized by rapid

growth and a higher risk of metastasis.

4. Undifferentiated Uterine Sarcoma: Poorly

differentiated or undifferentiated tumour, making it difficult to determine its

tissue of origin. This is a highly aggressive tumour with poor prognosis.

Both categories share some overlap (like

undifferentiated uterine sarcoma), they focus on different aspects of uterine

sarcomas and employ different criteria for classification.

Trends

Although uterine cancer is the most common

malignancy affecting the female reproductive system, uterine sarcoma accounts

for only a small part of these cases. It is estimated that uterine sarcomas

represent approximately 3 to 5 per cent of all uterine tumours and about 1 per

cent of malignancies affecting the female genital tract. In India, the

incidence of uterine sarcomas is still low compared to endometrial carcinoma,

but trends show a gradual rise in uterine malignancies due to changing

lifestyle factors, hormonal influences, and delayed childbearing. Uterine

sarcoma primarily occurs in postmenopausal women normally around 50-60, with

risk factors including prior pelvic radiation therapy and certain genetic

predispositions.

Method of Metastasis

Uterine sarcoma can be highly aggressive

and metastasising to other parts of the body, such as the lungs, liver, or

bones. This process occurs when cancer cells break away from the primary tumour

in the uterus and travel to distant sites through the bloodstream or lymphatic

system.

Cancer cells grow and invade nearby tissues

within the pelvic area, such as the cervix, bladder, or rectum is referred as local

invasion. If cancer cells enter the lymphatic system, a network of

vessels and nodes that helps fight infections, known as lymphatic spread.

They can travel to nearby or distant lymph nodes. Whereas cancer cells may enter

the bloodstream and can be carried to distant organs, such as the lungs, liver,

or bones is considered as haematogenous spread. Establishing

Secondary Tumours means the cancer cells settle in new locations and

begin to grow, forming secondary tumours.

Common sites of

metastasis

Uterine sarcoma often metastasises to the

lungs, liver, bones, and peritoneal cavity. Once uterine sarcoma spreads to

other parts of the body, it is considered advanced or metastatic cancer. The

prognosis worsens when uterine sarcoma metastasises because it becomes more

difficult to control and treat. Early detection and treatment are crucial to

limit the spread and improve outcomes.

·

The lungs are the most frequent location where

uterine sarcoma spreads, causing symptoms such as shortness of breath or chest

pain.

·

When cancer cells metastasize to the liver, they

may travel through the bloodstream, leading to symptoms like jaundice or

abdominal swelling.

·

Bone metastases can result in severe pain or

fractures due to the formation of secondary tumours in the bones.

·

Additionally, the cancer may spread locally to

the abdominal lining also known as peritoneal cavity, further complicating the

condition.

Risk Factors and Recurrence

Women who have a higher number of menstrual

periods during their lifetime have a greater risk of developing uterine cancer.

Other risk factors include

Ø

Genetic Factors

Ø

Tamoxifen use; for breast cancer treatment, has

a weak oestrogen-like effect on the uterus

Ø

Obesity; excess fat tissue converts androgens

into oestrogens

Ø

Age and Menopause; most cases diagnosed in

postmenopausal women and over 50 years

Ø

Diabetes and Hypertension; Fatigue, weight loss,

and general malaise may indicate metastasis

Uterine sarcomas have an aggressive

clinical behaviour with a tendency to local recurrence and distant spread. The

local recurrence of uterine sarcomas within the pelvis after treatment is high,

even if the initial neoplasm is surgically removed because sarcomas usually

invades surrounding tissues. The recurrence often occurs within 2–3 years of

initial treatment.

Symptoms

The symptoms of uterine sarcoma are often

non-specific and can overlap with other conditions. Both uterine sarcomas and

leiomyomas have similar symptoms. Not all women with these symptoms have

uterine sarcoma, though require medical attention.

v

Most common symptom is irregular vaginal

bleeding, especially in postmenopausal women

v

Unusual, watery, or blood-tinged vaginal

discharge

v

Pelvic and abdominal pain due to tumour or

spread or local recurrence

v

Changes in urinary and bowel habits

v

Palpable mass may be felt in the pelvis or lower

abdomen

v

Fatigue, weight loss, and general malaise may

indicate metastasis

Allopathic Treatment

Uterine cancer treatments in allopathy vary

based on the type, stage, and aggressiveness of the disease. However, uterine

cancer is often treated with surgery and in metastasis cases, particularly

uterine sarcomas, involve more aggressive and sometimes irreversible

treatments. In radical hysterectomy the patient has been undergoing complete removal

of the uterus and surrounding tissues. Similarly, radiation therapy and

chemotherapy can result in significant physical and emotional suffering,

including infertility, persistent hormonal imbalances and chronic pain. Despite

these aggressive treatment methods uterine sarcoma often have high recurrence rates

and poor survival outcomes.

Homoeopathy Remedies for Uterine Cancer

Homoeopathy adopts a different treatment

approach in disease treatment compared to allopathy. Instead of focusing the

disease, homoeopathy takes a holistic approach aiming to stimulate self-healing

capacity of our body. This system of medicine views health as a balance of the

vital force, and any disruption to this balance manifests as disease symptoms.

Therefore, the focus of homoeopathic treatment lies in restoring this balance,

addressing the root cause rather than merely alleviating the symptoms. As a

result, it ensures minimal side effects and encourages the body to recover

naturally.

Homoeopathy also considers the metastasis

condition of uterine cancer uniquely. It believes that treating symptoms alone

may suppress the condition, potentially driving it deeper into the system.

Instead, it aims to eliminate the underlying imbalance to achieve overall

health. By focusing on restoring harmony in the vital force, homoeopathy not

only addresses the disease but also promotes overall health and resilience.

Homoeopathic remedies act at a cellular

level, modifying pathological changes by improving cellular energy dynamics,

reducing oxidative stress and promoting programmed cell death (apoptosis) in

abnormal cells. These effects prevent the unregulated growth of malignant cells

and promote the repair of damaged tissues. The remedies also influence

epigenetic mechanisms, which regulate gene expression without altering the

underlying DNA sequence. By doing so, homoeopathy aims to correct genetic

imbalances that contribute to the progression of cancer.